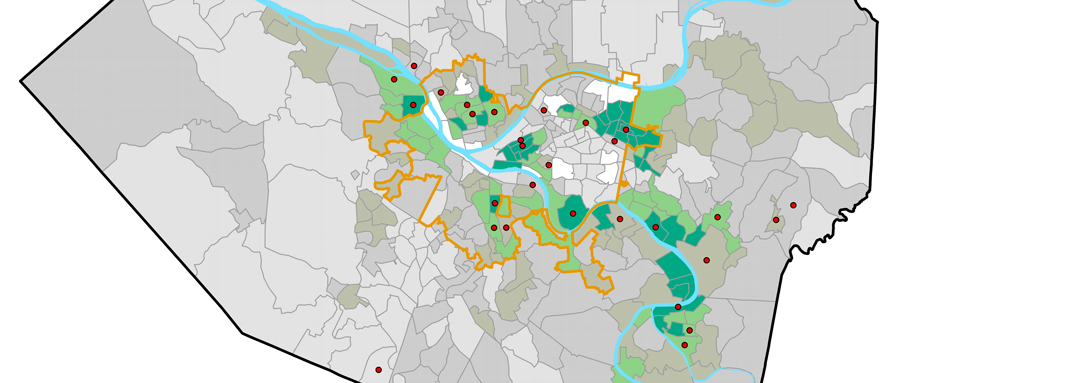

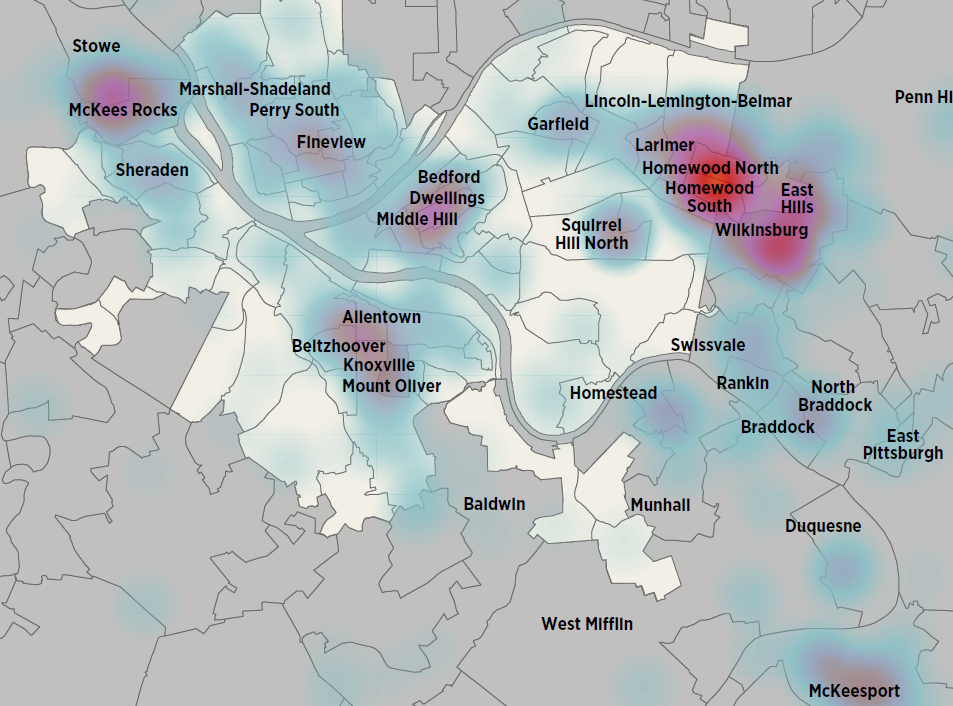

The Alternative Response Initiative provides emergency intervention by trained behavioral health and social services professionals instead of—or in addition to—police or EMS for eligible 9-1-1 calls. During non-violent crises, these professionals offer de-escalation, support and connections to resources. The program aims to (1) reduce strain by strengthening emergency capacity and (2) deliver trauma-informed, client-directed and compassionate responses, positioning the emergency response network to serve the public promptly, efficiently, thoughtfully and effectively.

DHS invites you to explore this page and the interactive dashboard to learn about the Alternative Response Initiative.

Dashboard Content

The Alternative Response Initiative Dashboard has seven tabs:

-

- Home functions as the entry point to the dashboard, outlining the program’s purpose and orienting users to the focus of each tab.

- About the Program describes the Alternative Response Initiative, outlining the program’s goals, operations and service regions.

- About the Data identifies the data sources used in this collection of dashboards and clarifies what information each source provides.

- Engagement Pathways details response types, illustrates sequence of actions and interactions across the response network from start to finish, and provides explanations for frequently asked questions regarding program protocols and practices.

- Requests and Responses is an interactive tab that displays call volume over time, response types, call types and time spent at each step.

- Interventions and Outcomes is an interactive tab that displays metrics on interventions teams provide, how situations resolve and the outcomes that follow.

- Demographics and Client Volume is an interactive tab that visualizes call volume over time and allows users to examine differences in demographic groups.

The dashboard updates monthly and presents data since October 15, 2024—the start of the Alternative Response Pilot program.

How the County Uses this Information

The county uses this information to:

-

- Track emergency response needs across communities over time to understand shifts in demand.

- Identify disparities in access and engagement to ensure the program meets residents where they are, equitably.

- Make data-driven decisions in practices and policies that align with observed community needs.

- Strengthen transparency and build shared understanding of the program for Allegheny County residents

For the best experience, we encourage exploring the dashboard on it’s full site. You can view it directly here.

Questions or Feedback?

We welcome your questions and suggestions. To share feedback, you can reach us at DHSResearch@alleghenycounty.us. If you’d like to stay informed, consider signing up for our newsletter. To learn how to use DHS data in your research, please visit our Requesting Data page. Thank you for your time and interest. Your engagement helps shape and improve how we share data that matters.